Educating incarcerated young people – a case for social justice

A team of researchers from Victoria University (VU), University of Tasmania and Deakin University have identified the challenges of educational provision in youth justice centres.

For children and young people who are in prison, whether on remand or sentenced, access to education is crucial. The research has therefore also identified how improvements can be made.

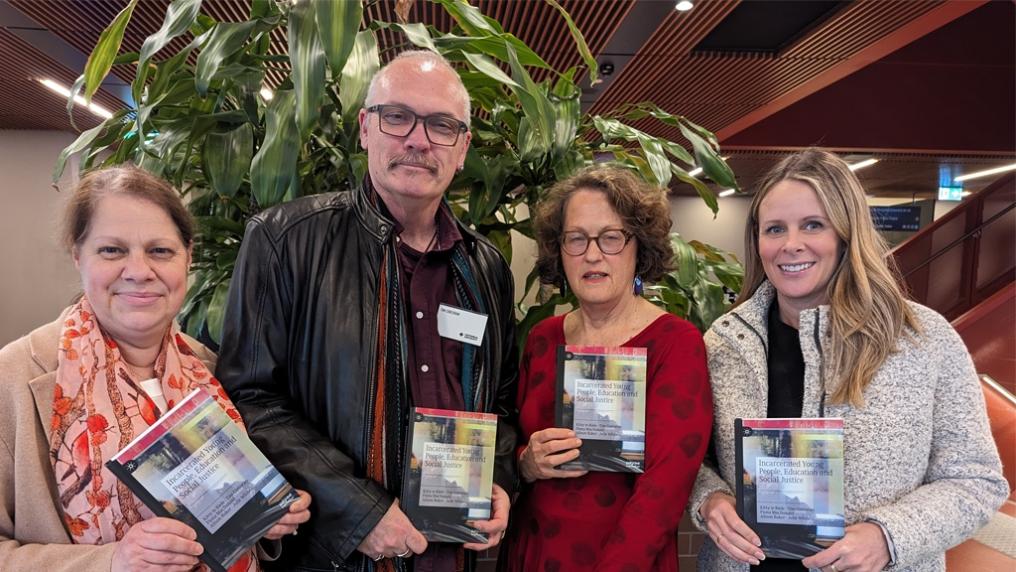

The culmination of three major research projects spanning eight years, Incarcerated Young People, Education and Social Justice was launched in Melbourne last night.

Researchers analysed interviews from key stakeholders in youth justice and education, rare interviews with young people in custody, and extensive documents, providing one of the most comprehensive reviews of education within youth justice in Victoria.

Lead author, University of Tasmania’s Professor Kitty te Riele, said the research demonstrates how access to high quality education in youth prisons benefits both the young people and the wider community.

“Young people are highly motivated to go to school when they are in prison. They are keen to learn new skills and know it is their ticket to better opportunities after they leave,” Professor te Riele said.

But it isn’t as simple as just putting a school in a youth justice centre. Young people in prison often have experienced poverty, trauma, learning difficulties, and suspension or exclusion from previous schools. Schools and other services inside youth custody need to provide support to ensure students are able to learn.

The conditions of custody create particular challenges, such as the allocation of students to classes based on security considerations, and the requirement that students be escorted to class by security staff.

Honorary Professor Julie White from VU said there is an urgent need for time in custody to be used constructively for learning.

“Schooling should be prioritised over security systems and staffing challenges,” Professor White said.

Deakin University’s Associate Professor Tim Corcoran pointed out that a young person’s connectedness with education can be disrupted due to misrecognition.

“This means they do not feel respected, valued, and safe. To redress this, schools inside custody and in the wider community must invest in genuine care which takes time and effort,” he said.

The authors identified three main areas for Australian and international youth justice settings to focus on in the short and long term, to provide an effective education experience for those in custody.

Fair distribution: access to material learning resources (e.g., books, computers) and a broad and relevant curriculum, as well as access to excellent teachers and sufficient instructional time.

Respectful recognition: countering the demonising of young people in prison as well as attending to the specific experiences of young people with different backgrounds, such as First Nations students or young women in prison.

Enabling representation: listening to what young people have to say about their past and current learning, and providing opportunities for students to contribute their views without forcing them do so.

VU’s Associate Professor Alison Baker said the right of children to have a say on issues that affect them is a significant part of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

“But prison is a location where most rights around choice and participation are taken away. Children and young people in custody are, first and foremost, human beings who all have their own interests, strengths, and aspirations,” she said

Associate Professor Fiona MacDonald also from VU said there is a need for high-quality education in youth custody to be supported by everyone and the media, politicians and the wider community all have a role to play.

Professor Julie White said the book demonstrates not only the challenges but also the possibilities for education as a mechanism for social justice for incarcerated young people.

We hope this book becomes a useful resource for the sector to continue to improve the education offering not just in Victorian youth justice centres, but in similar settings around the world.

Following the formal launch, the team will share the book with relevant policy makers.

The projects were funded by the Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation, the Victorian Department of Education and Parkville College.