Crunching the number: Exploring the use and usefulness of the Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR)

The transition from school to post-school life and tertiary study has never been more important.

The world, including how we learn and work, is changing rapidly. More people are undertaking tertiary education – either vocational education and training or university study - than ever before. Higher levels of education will be required for many jobs in the future.

But there is confusion over how to best support young people to move from school, to further study and training and on to meaningful careers. And at the centre of this lies the ATAR.

There is a growing disconnect between the role ATAR plays in schools and universities.

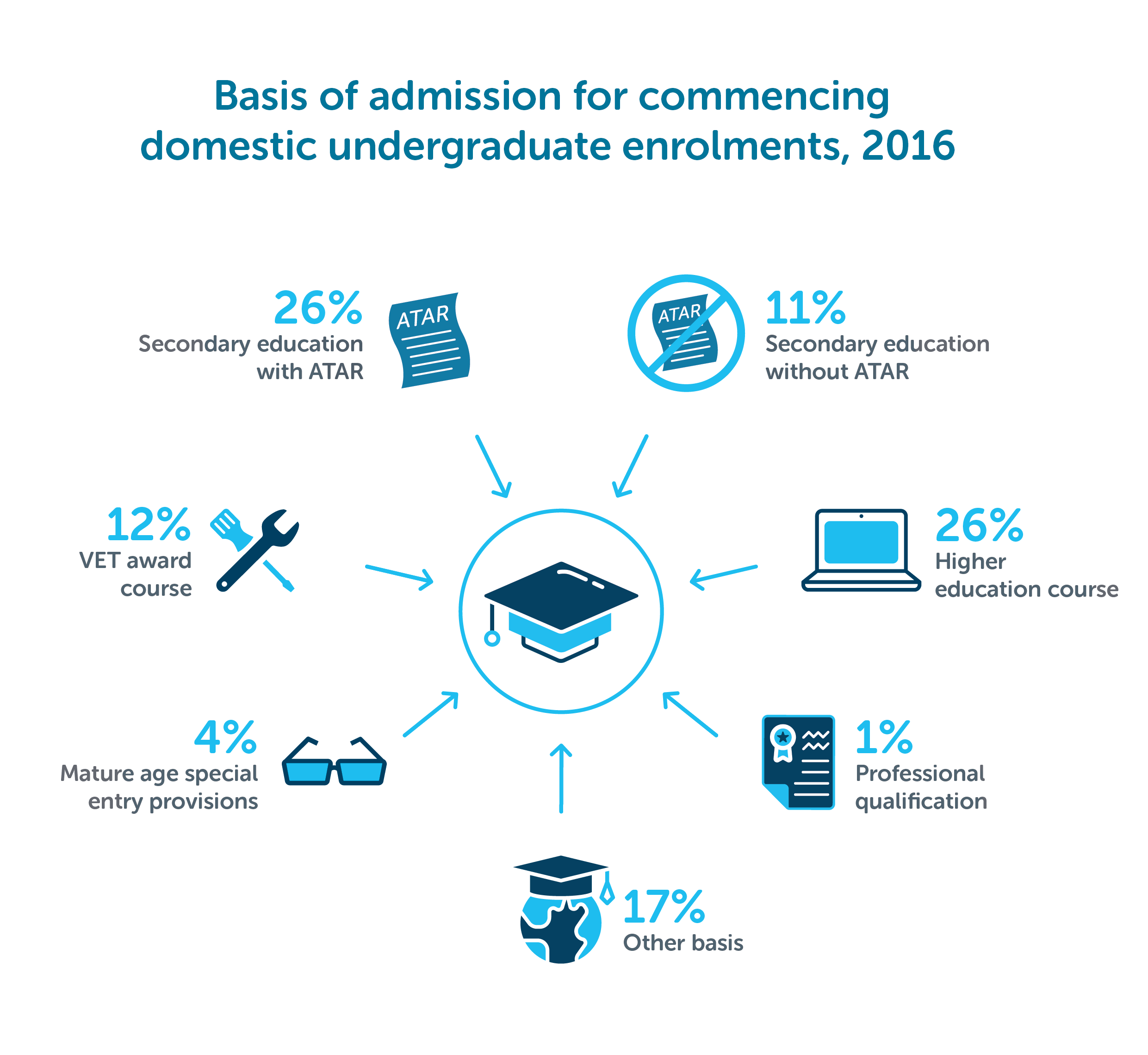

Only one in four domestic undergraduate students were admitted to courses based on their ATAR in 2016, down from one in three in 2014. This is at odds with the message reinforced by schools, families and the media – that the ATAR is everything.

This disconnect with the ATAR exposes a system that is not working cohesively, and holding back many young people from making good transitions from school to the world beyond.

It is time to look across our education system, decide what we want it to deliver for young people, for communities and for our future economy and rethink what role, if any, the ATAR should play.

What is the ATAR?

The Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR) is a ranking between 0 and 99.95 of year 12 students’ results across Australia in a given year. It was designed for universities to sort and select students but has evolved to have a much broader reach – many students and parents now see it as the key way of measuring success at the end of school.

The ATAR presents a challenging policy dilemma. It serves a number of purposes such as measuring student success and facilitating access to university, and there are a range of individuals and institutions with a stake in the system, including universities, schools, students and families.

To move forward, we need to acknowledge that secondary and tertiary education form part of one ongoing learning pathway – and any reforms need to start by recognising this.