Education is better off with the states

Could we be witnessing the dawn of a new era of education federalism?

It’s rare to hear senior public servants severely and publicly criticise existing institutional and political arrangements and call for dramatic change. But recently Richard Bolt, Secretary of Victoria’s Department of Education and Early Childhood, publicly called for an end to Commonwealth domination of the national education ministers’ meetings. The Commonwealth’s role in school education should be “largely non-directive”. Leadership, he said, should instead come from the states.

While some of Bolt’s comments have been briefly mentioned in the press, their full significance seems to have been missed. The states are often loath to bite the hand that feeds them, which is why these comments were so remarkable.

Could the state governments be emboldened by the High Court’s ruling that the Commonwealth lacks the authority to make direct payments for school chaplaincy programs? Or enraged by the May budget, which reduced expected future payments to the states by $80 billion?

Bolt described the school funding and policy settlement, in which the states and the Commonwealth each fund both the public and private school sectors yet make decisions independently and pursue competing policy solutions, as “very dysfunctional”. The crossover in government funding roles, he said, was not deliberate, harmonised or routinely managed. And the absence of strategic collaboration on school funding allocations had produced “incoherent” and “inequitable" results.

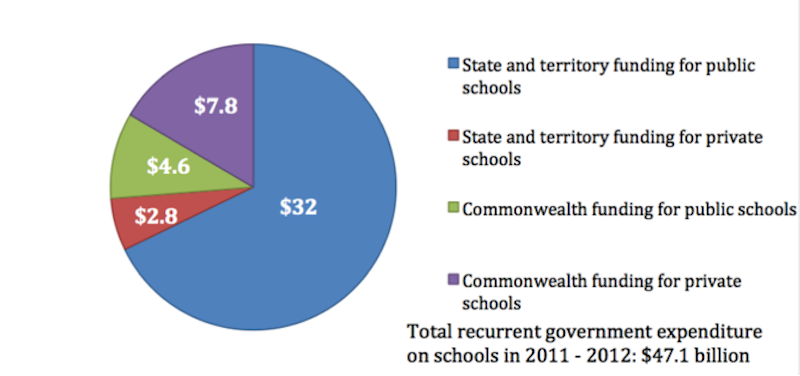

Recurrent school expenditure by sector and level of government, $ billions, 2011-2012.

Data source: Productivity Commission 2014 Report on Government Services, Chapter 4: School Education table 4.1

Infographic text alternative:

Pie chart showing the following allocation of recurrent school expenditure by sector and level of government 2011-2012:

- State and territory funding for public schools - $32 billion

- State and territory funding for private schools - $2.8 billion

- Commonwealth funding for public schools - $4.6 billion

- Commonwealth funding for private schools - $7.8 billion

The total recurrent government expenditure on schools in 2011-2012 was $47.1 billion.

The Gonski Review of School Funding investigated and advised on this muddy mess. But the Gillard government insisted on keeping the funding streams for public and private schools separate, perpetuating these problems.

It gets worse. The general, recurrent funding from the Commonwealth to the states to run schools and other essential services are not guaranteed income streams. They are at risk of being turned off or reduced, which is not conducive to good policy.

Bolt’s greatest condemnation was directed at “fixed-term, grafted-on federal grants programs” or “gravy trains passing by with short-term gifts”. These projects have received vast amounts of new money over the last decade. Bolt says this has been “largely wasted”.

[Victoria’s] view is that sustained impact is best achieved by schools strategically focusing on better learning and devoting their ongoing core funding to achieving their plans … unilateral federal grant projects seriously undermine such a model. They distract attention from schools’ priorities to the short-term preoccupations of the Commonwealth…they divide accountability and dilute focus [and] have had no tangible or measurable result.

Bolt’s views are shared by external policy and federalism researchers and are well supported by evidence. Even the Gonski review bluntly stated that states and the non-government school system authorities

are better placed than the Australian government to determine the most effective allocation of available resources in their particular circumstances.

When it comes to schooling, states – with over 140 years' experience and direct connections to schools and teachers – are simply much better placed to develop, implement and assess policies to improve learning.

Australia’s federal system offers a natural laboratory for states to try new ideas, or adapt existing ideas to better respond to local needs and priorities. Commonwealth directives limit innovation and restrict the ability of states and schools to tailor programs to best meet their students’ needs. National uniformity results in what Bolt describes as “lowest common denominator reforms, or no reforms”.

Studies of federal interventions in schooling via tied grants throughout last century in Australia and the United States have found that, for the most part, these either failed to achieve the desired outcomes, had unintended negative consequences, or were impossible to assess.

To a large extent, the states are already driving schooling policy in Australia. The school policy centrepieces of both major parties at the last two federal elections - such as greater power for school principals, and the needs-based funding model - were taken from state governments where they had been in place for up to 20 years.

Complete separation of the activities of two levels of government in schooling is unlikely, unfeasible and undesirable. Joint planning and strategic collaboration, led by the states but supported by the Commonwealth where appropriate, could enhance learning outcomes, equity, accountability, productive competition and funding efficiency.

For this to occur, the Commonwealth should cease almost all of its fixed-term, ad hoc grant programs and roll the funding into the general recurrent funding for schools. Better yet, this general funding could then be rolled into a large, untied grant to each state, such as the GST “cash back” grant.

The recommendations of the National Commission of Audit and the White Paper on the Reform of the Federation provide an opportunity to recalibrate government roles in education.

Alas, we are unlikely to see radical change. Despite the Abbott government’s rhetoric about cutting expenditure and reducing Commonwealth command and control, its first budget saw a sizeable increase in bureaucrats in the federal education department, and further restrictions attached to tied grants for schooling. These grants continue to grow in number, with $22 million for Direct Instruction for a few years in 50-60 hand-picked schools, which subscribe to a list of conditions, being just the latest example.

This is unsurprising. Each Commonwealth government since Menzies has intervened more in education than the last. It is just too electorally popular and ideologically compelling.

This article was originally published on The Conversation on 23 July 2014.

Read the original article.

Image courtesy of Michael Coghlan, Flickr Commons