A model for tertiary education funding in Australia

Mitchell Professorial Fellow Peter Noonan proposes a new model for tertiary education funding in Australia, in a presentation delivered to the Australian Financial Review Higher Education Summit on Wednesday 28 October 2015.

I would like to thank the Australian Financial Review for the opportunity to speak at this year’s Higher Education Summit.

Today I would like to:

- explain why we need to consider funding in the context of the broad tertiary education sector

- briefly recap the financing model proposed in the Mitchell Institute paper Financing Tertiary Education in Australia

- illustrate some of the issues and challenges we face with relevant and updated data

- reflect on developments subsequent to the release of the paper and outline our thinking in terms of how that model might now be refined.

Recent developments & the current situation

The two major developments subsequent to the release of our paper are:

- the outcomes of the COAG leaders retreat which raised the prospect of the Commonwealth assuming full responsibility for Vocational Education and Training (VET) funding

- the recent decision by the Commonwealth Government to not proceed with its proposed higher education funding reforms for 2016, and to engage in a further process of consultation and policy development on reform options.

I believe that these two processes now create an important opportunity and the policy space for the Commonwealth to consider the development of a coherent funding framework for tertiary education across the higher education and VET sectors.

There are some promising signs in this regard:

- The reintegration of VET into the education portfolio

- The appointment of Minister Birmingham with his understanding of VET as the Minister with overall responsibility in both sectors

- The treatment of these issues in the Federation Reform Discussion paper

- The outcome of the National Reform Summit, which indicated that VET should be made a national priority by developing a broad tertiary model valuing VET and higher education.[i]

It would be unfortunate, and a missed opportunity if we were to revert to previous practice by dealing with funding in each sector separately.

Historic separation of VET & higher education

While the term tertiary education has been used in Australia for many years the higher education and VET sectors have followed distinct trajectories in the past few years.

However, in 2008 the Bradley Review argued:

What is needed is not two sectors configured as at present, but a continuum of tertiary skills primarily funded by a single level of government and nationally regulated which delivers skills development in ways that are efficient, fit for purpose and meet the needs of individuals and the economy.[ii]

Although the Rudd and Gillard Governments moved quickly and comprehensively on the core recommendations of the Review as they applied to higher education, and have transformed that sector, as a result the important recommendations that were designed to give effect to the Review’s conception of an integrated tertiary education system were largely overlooked.

In recommending the adoption of the demand driven higher education system the Bradley Review also argued that:

‘... some states and territories face major fiscal constraints, which may lead them to reduce the investment in VET in the near future, leading to skewed and uneven investment between the sectors over time if a demand-based funding model is adopted for higher education’.[iii]

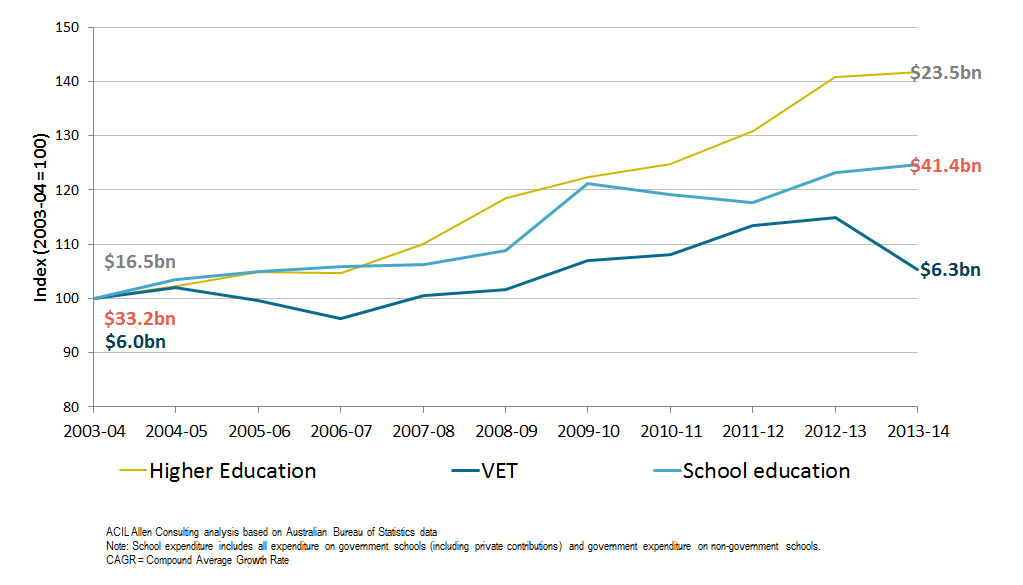

This finding was unfortunately prophetic, as analysis by the Mitchell Institute of public expenditure through the schools, VET and higher education and between jurisdictions on VET illustrates.[1]

Expenditure on education and training in Australia, 2003-4 to 2013-14

Text alternative: Graph showing 2003-14, where Higher Education expenditure grows from $16.5bn to $23.5bn (highest growth curve); VET from $6bn to $6.3bn (lowest growth curve); and School from $33.2bn to $41.4bn. ACIL Allen Consulting analysis based on Australian Bureau of Statistics data.

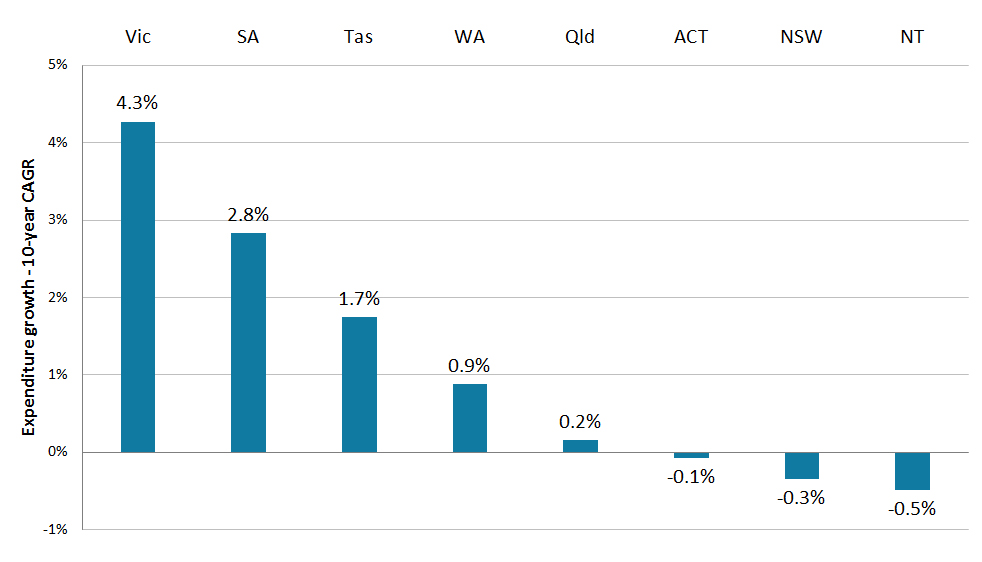

VET expenditure 2003-2013

Text alternative: Bar graph shows expenditure growth 10-year CAGR: Vic 4.3%, SA 2.8%, Tas 1.7%, WA 0.9%, Qld 0.2%, ACT -0.1%, NSW -0.3%, NT -0.5%; ACIL Allen Consulting based on NCVER VET Finance Report

Reconceptualising tertiary education

The Mitchell Institute tertiary education program commenced with a lecture by Professor Peter Dawkins, the Vice Chancellor at Victoria University (a dual sector institution) in May last year.

Peter argued that we needed to reconceptualise tertiary education in Australia in two ways: (i) as a universal system to complement near universal secondary education, and (ii) as a more coherent system across the VET and higher education sectors.[iv]

At the outset, however, it is important that we clearly define what we mean by tertiary education.

At the Mitchell Institute we have defined tertiary education in Australia as encompassing AQF Certificate III to post graduate programs. This is a broader approach than the previous definitions of tertiary education, which only encompassed VET Diplomas and Advanced Diplomas and higher education sub degree and degree programs, but narrower than the Bradley Review, which considered the whole of the VET sector as part of the tertiary system.

The broader approach is appropriate because our tertiary system must work efficiently and effectively across the full range of qualifications, and be highly responsive to the emerging needs in the modern labour market, and the changing needs of individuals over the course of their adult lives.

The accessibility and effectiveness of the tertiary education system will determine whether or not individual Australians – both younger and older – gain the skills, knowledge and capabilities required for effective participation in the modern knowledge intensive economy, as well as the passion for further education throughout their adult lives.

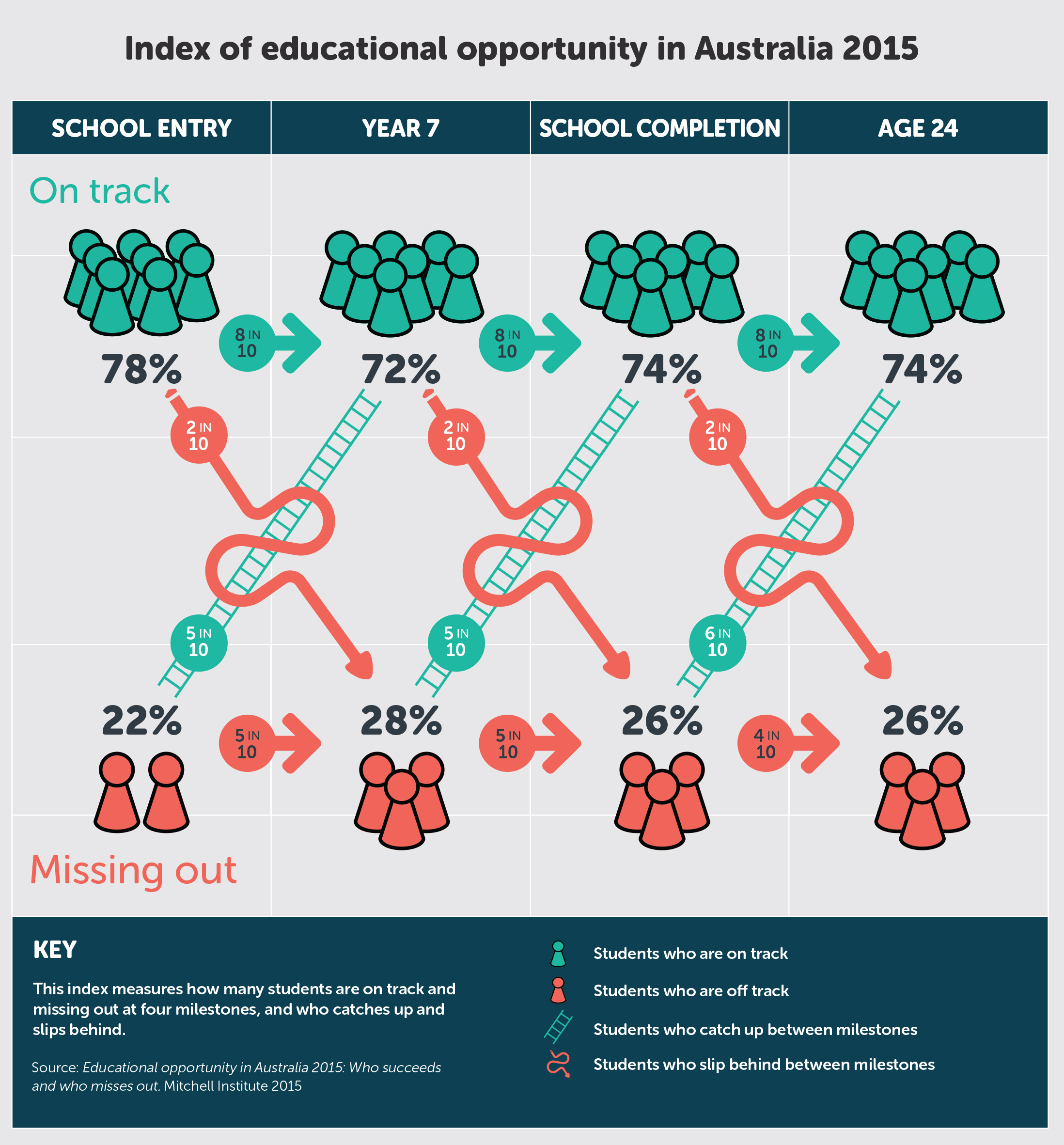

Findings from Educational Opportunity in Australia 2015

I would like to briefly highlight some critical outcomes from the major report Educational Opportunities in Australia released by the Mitchell Institute on Monday.

That report comprehensively demonstrates for the first time how young people fare at critical transition points across our entire education system, from preschool to tertiary education.

It shows that the system works well for many if not most students, that students who do fall behind at some key transition points can recover, and that students who are on track can still fall behind at key milestones.

Of greatest concern is that many students who are behind when they commence formal schooling never recover and fall further and further behind.

Text alternative: Index of educational opportunity in Australia 2015 shows how many students are on track and missing out at four milestones (school entry, Year 7, school completion, age 24). On track: 78% at school entry, 72% Year 7, 74% school completion, 74% age 24. Missing out: 22% at school entry, 28% Year 7, 26% school completion, 26% age 24. Slipping between the milestones: 2 in 10 each milestone. Climbing between the milestones: 5 in 10 each milestone up to school completion; 4 in 10 between school completion and age 24.

As a consequence of this systemic failure, by age 24, 26 percent of young people have not made a successful transition to full time tertiary education or the workforce.

Redressing this failure must be the major policy priority for Australian governments, not just for equity reasons, but because of the consequences of tens of thousands of Australians being locked out of meaningful and sustained economic and social participation.

As our tertiary financing paper said:

Today’s young Australians are growing up at a time when a post‐school qualification is becoming a baseline requirement for meaningful social and economic participation. It is critical for them, and all of us, that they are equipped with the skills and capabilities they will need to thrive in an increasingly competitive, global economy.

A new model for financing tertiary education in Australia

Our work at the Mitchell Institute to date has focused on building a new, coherent and sustainable model for financing tertiary education.

The shortcomings in the current financing framework for tertiary education - between the VET and higher education sectors and between jurisdictions - results in:

- differential treatment of students

- inconsistency in eligibility, subsidies and fees

- inconsistent access to income contingent loans

- inconsistent access to student income support

- widening investment gap between higher education and VET

- a growing gap in per student funding levels

- potential distortion of student choice

- diminished overall effectiveness of the tertiary education system.

It is encouraging that the Reform of the Federation Discussion Paper confirmed and reinforced the points made by Mitchell, concluding that:

As result, funding duplication and overlap can create perverse incentives that can affect the choices of students and learners and, sometimes, drive the behaviour of governments and providers – rather than working on the basis of whether it will lead to a job or further learning.[v]

The future of the demand driven higher education funding system, including its possible extension to sub degree programs, future funding levels for the VET system and eligibility for access to subsidised courses and to income contingent loans are therefore inextricably linked.

The Mitchell Institute’s tertiary financing work has centred on the principle of a ‘student entitlement’ to tertiary education, implicit in the demand driven higher education funding system and the student entitlement for the VET sector agreed to by the Council of Australian Governments in 2009.

Some may quibble at the concept of an entitlement and its implications in a highly constrained fiscal environment where governments are noticeably reluctant to commit to new spending, particularly spending linked to automatic program eligibility.

However, the mechanism is less important than the goal of seeking to achieve near universal participation in tertiary education or training.

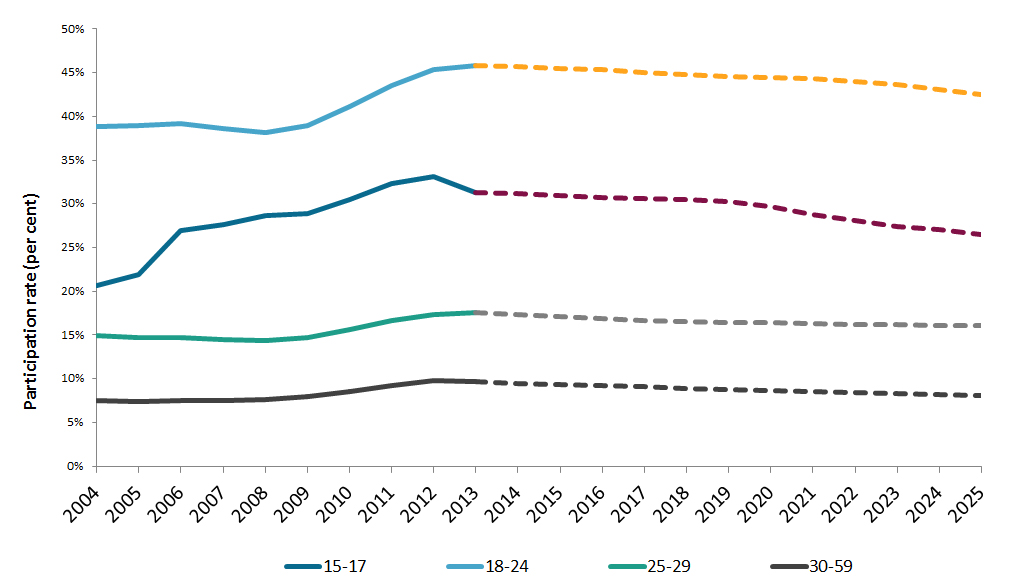

Australia’s current participation rates in tertiary education will slide if we don’t increase enrolments as a consequence of population growth, let alone addressing the needs of those who are currently missing out.

Projected participation rates (when enrolments kept constant at 2013 level)

Text alternative: Line graph shows age participation rates to 2014 and predicated changes to 2025. Some growth 15-24 age group to 2014, then minor declines; mostly flat 25-59 age group.

Our investment in schooling is also diminished if young people on leaving school are not able to secure a place in a high quality tertiary education system: in terms of their overall educational needs, merely completing school is a job half done.

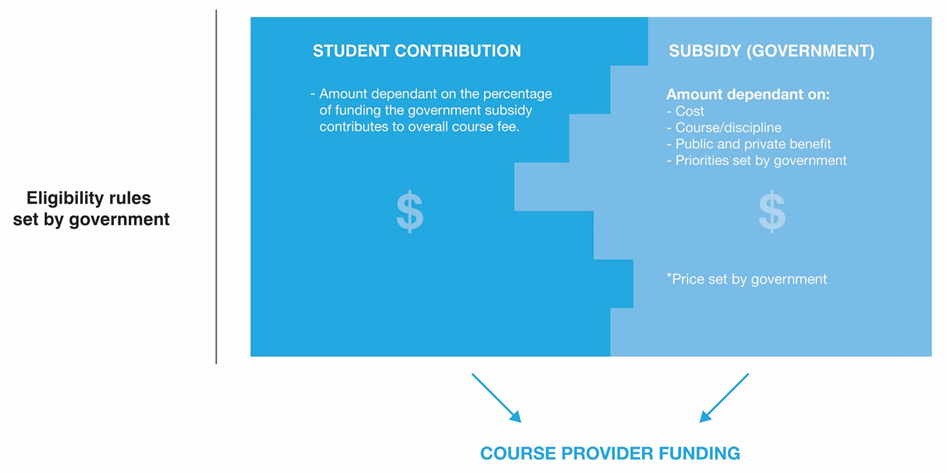

The model outlined in the Mitchell Institute’s tertiary financing paper identified the core elements of a tertiary education entitlement, as comprising a public subsidy and a student contribution, that together constitute a price paid to a provider based on the course in which the student was enrolled.

This is a representation of the current higher education and VET financing systems, in terms of how per student funding levels are set for providers.

Components of a tertiary entitlement

Text alternative: Graph 'Eligibility rules set by government' shows Student contribution (amount dependant on the percentage of funding the government subsidy contributes to the overall course fee) + Subsidy (amount dependant on cost, course discipline, public/private benefit, priorities set by government)* = Course provider funding. *Price set by government

Further reflecting current funding approaches, the balance between the public subsidy and the student contribution in each sector could:

- be set on a fixed proportional basis, with subsidy and fee levels varying according to course cost

- vary according to the assessed public and private benefit flowing from different courses, but with prices paid to providers still based on a relative course costs

- vary between providers based on consistent subsidy levels per course, but varying fee levels reflecting differing provider costs and the value each provider offered students

- vary between providers based on adjustments to subsidies where revenue from student contributions exceed specific thresholds.

The paper also highlighted the very different eligibility criteria applying to access a student entitlement between VET and higher education and between jurisdictions in relation to VET.

Under the proposed model the eligibility rules for access to the entitlement would, as at present, be set by government, but are also conditional on provider entry requirements particularly in higher education.

To address the problem of investment in VET, the paper looked at three options to assign clear responsibility for financing tertiary education across the State and Commonwealth Governments:

- full Commonwealth responsibility for higher education and VET funding

- each level of Government taking responsibility for a particular set of qualifications

- the states and territories taking full responsibility for VET.

The paper identified full Commonwealth funding responsibility for tertiary education as the optimum model, but at the time assessed that that option was not likely to be agreed.

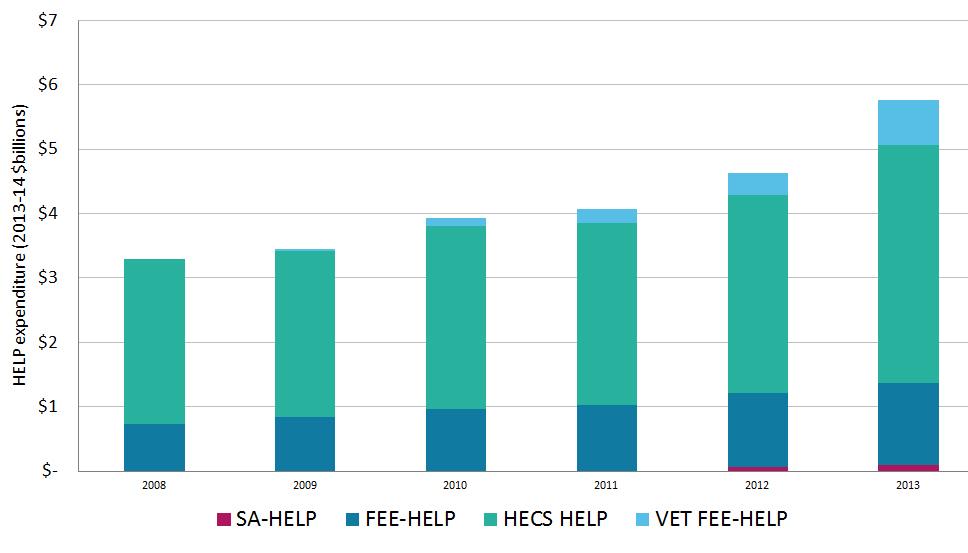

Expenditure through the different income contingent loans schemes is rising rapidly with significant growth in VET FEE HELP, but with very poor design and outcomes.

It therefore proposed an alternative, under which the Commonwealth would assume responsibility for funding Diplomas, Advanced Diplomas and Associate Degrees in VET and higher education (and of course degrees) with the States funding Certificate level programs and the Commonwealth operating a single ICL scheme across the tertiary sector.

This option was in part driven by the proposed extension of demand driven higher education funding to sub degree higher education programs.

I have strongly supported this measure, but if implemented without addressing declining investment in VET it would most likely result in the progressive transfer of VET sub degree programs into the higher education sector – that is the Commonwealth would assume full funding responsibility all sub degree and degree programs as an unintended consequence.

A key principle of our model was that no tertiary student should face upfront fees as a condition of participation - a long standing principle in higher education but currently only partially applied in VET as students in Certificate level courses cannot access an income contingent loan.

When VET fees were very low this was not a major issue in terms of the effect on participation, but with fees for many Certificate III and IV courses now ranging between $2,000 - $4,000, increasing numbers of VET students are treated quite differently and quite inequitably compared to other tertiary students.

Expenditure through the different income contingent loans schemes is rising rapidly with significant growth in VET FEE HELP, but with very poor design and outcomes. There is significant over-expenditure on qualifications by some providers rather than reasonable expenditure on a broader range of qualifications.

Our proposal therefore argued for a single and comprehensive income contingent loan system replacing the current five different schemes.

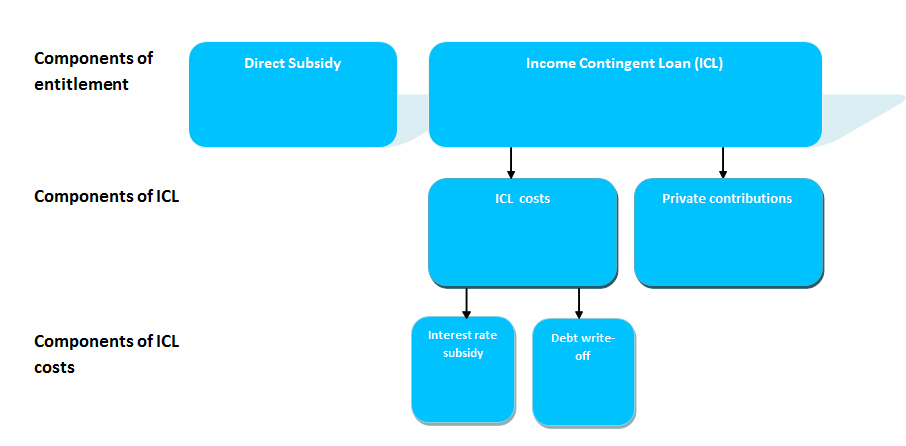

Costs of a tertiary entitlement

Text alternative: Graph shows components of entitlements (direct subsidy, income contingent loan abbreviated as ICL); Components of ICL (costs, private contributions); components of ICL costs (interest rate subsidy, debt write-off).

Higgins and Chapman’s modelling of income contingent loans

We asked Bruce Chapman and Tim Higgins to prepare a research report for us to model the structure and settings required to make a single income contingent loan scheme sustainable.

The Chapman Higgins paper provides for the first time a clear picture of the important relationship between direct public subsidies for tertiary courses, the level of student contributions and the public subsidies involved in the provision of income contingent loans to offset the upfront costs of student contributions.

Growth in Income Contingent Loans

It demonstrates that great care must be taken in how student contribution levels are set and funded through income contingent loans, as where loan amounts exceed students’ capacity to repay, significant public subsidies to providers in the short term and students in the long term are created.

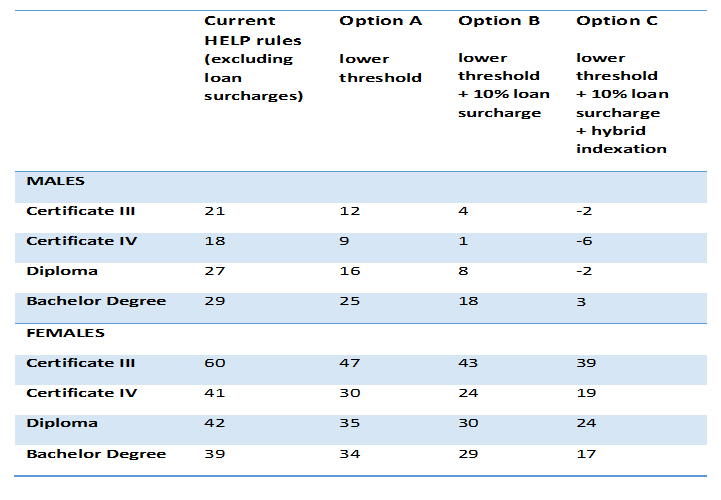

It also highlights the very different subsidies across qualification levels, and between males and females as a consequence of lower female workforce participation and the gender pay gap, particularly in relation to VET qualifications.

The paper models settings for a single income contingent loan scheme, aiming for a more equitable and sustainable system across student cohorts and qualification levels.

Summary of ICL subsidy ratios under combined options Government bond rate of five per cent

Text alternative: Bar graph shows increase in HELP expenditure 2008-2014 in billions, from over $3bn to over $4.5bn, with the greatest component HECS HELP, the second largest FEE-HELP. SA-HELP and VET FEE-HELP are small but increasing.

Text alternative: Current HELP rules (excluding load surcharges): Males: Cert III 21, Cert IV 18, Diploma 27, Bachelor degree 29. Females: Cert III 60, Cert IV 41, Diploma 42, Bachelor degree 39. Option A lower threshold: Males: Cert III, 12, Cert IV 9, Diploma 16, Bachelor degree 25. Females: Cert III 47, Cert IV 30, Diploma 35, Bachelor degree 34. Option B lower threshold + 10% loan surcharge: Males: Cert III, 4, Cert IV 1, Diploma 8, Bachelor degree 18. Females: Cert III, 43, Cert IV 24, Diploma 30, Bachelor degree 29. Option C lower threshold + 10% loan surcharge + hybrid indexation: Males: Cert III -2, Cert IV -6, Diploma -2, Bachelor degree 3. Females: Cert III, 39, Cert IV 19, Diploma 24, Bachelor degree 17.

A more integrated approach to subsidies & income contingent loans

The major point I want to make is that we have to treat the two different elements of tertiary education financing – the direct public subsidy and the subsidies from income contingent loan schemes in a far more integrated way.

Cutting direct public subsidies and increasing loan amounts without any regard to capacity to pay will result far less transparent subsidies, with the costs of meeting those subsidies coming from future government outlays.

Similar considerations arise under a model where the states fund VET courses and the Commonwealth operates an income contingent loans scheme. The states have an incentive to reduce subsidies and transfer costs to students, and over time to the Commonwealth unless the states share in the direct and indirect costs of the operation of the income contingent loan scheme.

Tertiary education financing is not a magic pudding. The costs of increased student contributions funded through income contingent loans must be met, either by individuals through additional time taken to repay debt, higher graduate salaries, increased loan subsidies or some combination of these.

Current policy landscape & the way forward

However as I indicated earlier the higher education reforms are now in limbo.

The key element of the higher education reform package – fee deregulation – is at best uncertain and it is difficult to see any government making a long term open ended commitment to demand driven funding based purely on current public subsidy levels.

The Commonwealth has not adopted a formal position on VET funding and different states are taking different views on the outcome of the COAG leaders retreat.

If we were designing HECS today it would be designed as a universal scheme, and there is no reason why we should not transition to one now.

The Australian Labor Party in its recent higher education policy statement indicated that it would not support the extension of demand driven funding to sub degree programs.

The Opposition is retaining its longstanding opposition to fee deregulation. It has in effect committed to current per student funding levels but not to the higher indexation levels introduced by the Rudd and Gillard Governments.

The Opposition has also signalled that it will not support the extension of demand based funding to higher sub degree programs, but has foreshadowed a further statement in this area.

It has also criticised Minister Birmingham’s advocacy for the Commonwealth to assume responsibility for VET funding, although this option was formally proposed and strongly prosecuted by the Hawke and Keating governments. [vi]

I must say I do not regard what is in effect a restatement of the status quo in relation to tertiary education funding as sufficient to meet the current and merging challenges faced by each sector and the tertiary education system as a whole.

There is however a major opportunity for the Commonwealth Government in a seemingly new and febrile policy environment to take a fresh look at the major issues involved, and for the Opposition to do the same in the run up to the election.

The funding issues facing the Commonwealth are at one level sector specific.

In higher education they include; the sustainability of the demand based funding system, its extension to sub degree programs and new provider categories, whether fee flexibility might be introduced and on what basis and future arrangements for research funding.

In VET they include; addressing the absolute decline in public VET funding and publicly funded VET enrolments and future arrangements for VET funding.

In my view these issues are interrelated and should be dealt with through an overall tertiary education funding policy, and preferably over time, a coherent tertiary education funding model.

For example, it is simply not possible to deal with future resourcing requirements for higher education and the future of the demand driven funding system (including its extension to sub degree programs) without considering the future capacity and role of the VET system.

The case for equitable treatment of all tertiary students in terms of access and consistent settings for income contingent loans is clear. We have consistent rules applying to citizens in relation to taxation, social security, Medicare, superannuation and the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

If we were designing HECS today it would be designed as a universal scheme, and there is no reason why we should not transition to one now.

While purists in the federation debate argue for the principle of subsidiarity in terms of decisions on what is funded and how, I am far more concerned about equitable treatment of students and the effectiveness of the tertiary education system in meeting the needs of national and increasingly international labour markets.

Students in each sector should be entitled to consistent levels of public support for similar qualifications, and informed demand, rather than funding incentives and disincentives, should drive provision.

This is not to say that the same system of public funding and eligibility should apply to both sectors. While there is growing convergence between the sectors and increasing partnerships between providers, the sectors largely serve different and complementary roles. They have different student populations and the nature of their qualifications and outcomes are also different. VET by nature is highly accessible and highly flexible in its delivery modes.

We need to maintain diversity and differentiation in tertiary education rather than see further homogenisation driven by prestige and funding.

However, the essential elements of the tertiary funding system:

- the direct public subsidy and the policies that underpin how subsidies are set and at what level

- the balance between public and private contributions

- the extent to which student contributions can be offset by income contingent loans

- the subsidies involved in income contingent loans

should in my view be determined on a consistent national basis.

If we think about the current arrangements, in effect we have two financing systems for tertiary education; one a direct subsidy system, the other in effect a combination of an insurance and investment banking system through income contingent loans.

Chapman and Higgins’ work and ongoing work by the Grattan Institute has shown we have to think more about how these two systems operate together.

In higher education the current public subsidy system has been found inadequate – both in funding levels, but also in the rationale for the current funding relativities between disciplines, in terms of purpose and their relationship to public and private benefits.

While fee deregulation has been proposed in part to address this problem, the risks of overpricing under fee deregulation, due to weak price signals to students and transfer of risk from providers to government under income contingent loans, are now widely recognised.

In VET the risks of poor market design, including the settings for VET FEE HELP are all too evident, low barriers to market entry and poor quality, in part linked to inadequate funding levels for many courses, are also evident.

My thinking - strongly influenced by the Chapman Higgins paper - is that we need to focus far more on loan levels for individual courses or disciplines - including potentially at the provider level - rather than uniform loan caps as a means of mitigating the risk of overpricing.

If income contingent loans were capped, either generally at course or disciple level, at the provider level or some combination of these, providers would be forced to think far more forensically and strategically about their pricing strategies if they wished to raise fees beyond approved loan levels.

Pricing guidelines, including clarity of purpose about the application of revenue from higher prices is also important. Some will no doubt argue that this process would interfere with institutional autonomy.

However, it should be born in mind that:

- revenue from higher student fees is paid to institutions immediately by government

- the whole system is underwritten by government

- significant public subsidies are involved, which will increase if fees do increase.

These factors more than justify the use of pricing guidelines to protect the public interest.

The alternative - price oversight - as proposed in my paper on the Pyne Higher Education reforms, is difficult to implement without going into detailed analysis of the price and cost structures of each institution.

In considering a future with a more fit for purpose tertiary funding system spanning VET and higher education, there are a number of contemporary public financing models to draw on, including the pricing of hospital services, the schooling resources standard recommended by the Gonski Review and the pricing of services and governance of the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

The key elements of this system and the steps involved in the development would be to:

- Treat the combined subsidy and student contribution as representing something akin to an efficient price for course delivery across the range of tertiary qualifications in both sectors.

- In the case of VET this could be fully funded by the Commonwealth, or if the states retain funding responsibility under a shared model, with clear contributions by the Commonwealth and the states. This is an alternative to the qualifications based funding model raised previously by Mitchell.

- Determine the balance between public and private contributions based on either public policy objectives or public and private benefit or some combination of these factors.

- Introduce a single and consistent income contingent loans scheme probably with lower repayment thresholds but with low repayments at the lowest threshold.

- Allow institutions, or in the case of VET systems, to vary the student contribution but place limits on income contingent loan amounts at the course or disciple level.

- This could also include adjusting the public subsidy level beyond specific thresholds.

Require institutions to follow consistent guidelines in price setting and the purposes to which revenue paid through income contingent loans beyond the efficient price can be applied.

These are only the broad elements of a tertiary financing system.

They are derived from the existing systems but seek to go back to first principles, clarify the purpose of each element of the system, link that element to an overall approach to price setting, allow for fee flexibility but more closely link student contributions to direct and indirect public subsidies, remove upfront fees for all tertiary students and provide a new framework for VET financing (should it remain a shared responsibility of the Commonwealth and the States).

At Mitchell we will continue to progress the development of this model, and are keen to receive feedback on it, recognising that there are a range of approaches and options available, each with advantages and disadvantages.

I also recognise that the model does not deal with the long term resourcing needs of each sector and the tertiary system as a whole.

It is of concern that the most recent Intergenerational Report forecasts a decline in expenditure on tertiary education as a proportion of GDP, although the forecasts only seem to relate to Commonwealth outlays and the assumptions behind the forecasts are not entirely clear.

I have continually argued that that needs to be modelled under a range of scenarios with a focus on, at a minimum maintaining participation rates, and beyond that moving to tertiary education becoming a near universal system for young people, with increased capacity for adult and workforce retraining and upskilling.

Thank you.

Endnotes

[1]Note that the data relates to total expenditure through public entities, not just expenditure on teaching and learning.

[i] National Reform Summit (2015) Summit Statement (August 26).

http://www.kpmg.com/AU/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/nation…

[ii] D. Bradley, P. Noonan, B. Scales and P. Nugent (2008) Review of Australian Higher Education, Canberra, 183

[iii] Bradley et al. 183

[iv] P. Dawkins (2014) Reconceptualising tertiary education: and the case for re‐crafting aspects of the Abbott Government’s proposed higher education reforms (PDF, 397.1 KB), Mitchell Institute, 14 May 2014.

[v] Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Reform of the Federation White Paper – Education Discussion Paper (2015) 69.

[vi] S. Bird MP (2015) Abbott Take-Over Of VET Will Only Mean Cuts, 12 September 2015.